After a late night drive from the Ramana Ashram to Kanchipuram, Vic and I slept late. When we left our hotel in the morning, hundreds of soldiers in tan uniforms blocked traffic near the Mutt. Thousands of people milled around, looking stunned, whispering and weeping. We didn’t know what had happened and couldn’t find anyone who spoke English, so we stood at the end of a line moving toward the Mutt.

After a late night drive from the Ramana Ashram to Kanchipuram, Vic and I slept late. When we left our hotel in the morning, hundreds of soldiers in tan uniforms blocked traffic near the Mutt. Thousands of people milled around, looking stunned, whispering and weeping. We didn’t know what had happened and couldn’t find anyone who spoke English, so we stood at the end of a line moving toward the Mutt.

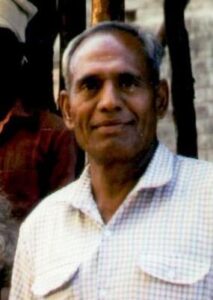

We inched forward, until we saw Powar. We’d never seen him on the street with his Indian military uniform. He was always inside guarding the sage in civilian clothes, but now he was helping with crowd control.

“What happened, Powar?” I asked even though I had guessed the answer. He looked down into my eyes, tears running along the ruts in his face and soaking his jacket.

“He’s dead, Madam. Our Swama-ji is dead.”

Powar didn’t hide his grief. No one did. We waited on the dusty street in the sun with the rich and poor, barefoot and gold-sandaled.

“Shoes, please. Shoes here,” the shoe man and his wife called out as we neared the gate. We handed our sandals over, knowing in this huge crowd we’d never see them again. We didn’t care.

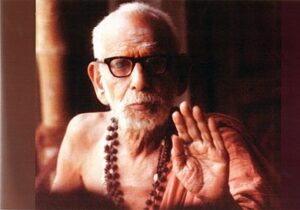

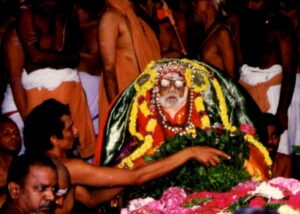

The hushed lines of grievers crept down the alley. The concrete platform where we’d sat as quiet meditators was filled with flowers and fruit and men. In the middle, surrounded by his closest male attendants, Sankara was seated in meditation posture on a raised chair. He was dead.

His body was draped in thick layers of colorful gold-threaded silks for which Kanchipuram was world famous. Where was the old sage in his thin cotton saffron robes? Gone.

His body was draped in thick layers of colorful gold-threaded silks for which Kanchipuram was world famous. Where was the old sage in his thin cotton saffron robes? Gone.

Vic and I shuffled forward in the line, our hands clasped in prayer over our hearts. To our left, the dead sage and his attendants. To our right, a temporary structure with a high roof to shade members of the temple.

I wanted to stop and spend a few more minutes with the sage, but so did everyone. I kept moving forward, one step at a time, soaking in the sorrow.

A familiar attendant kept the line moving down the alleyway. We made eye contact. He’d seen us waiting and meditating all week and knew us from our two earlier visits. He nodded to Vic and me. We nodded back. Then he beckoned us to come closer and leave the line.

“You stay with us,” he said, pointing toward the shaded area. “Yes, you stay,” he said again when I looked at him with questioning eyes. His eyes were swollen and red, but he was sure.

I moved toward a patch of shade above the flow of mourners. Vic pointed to his camera, asking if he could take photos and got a positive nod.

Vic went to the press box, but I stood a few steps above the alleyway with a clear view of Sri Sankara, the funeral ritual, and the lines of people who had come to pay respects.

The dead sage’s body seemed to emanate light, a soft glowing halo. Deep silence filled me as I focused on the Wise One and the stricken faces of his attendants. I sank deeper into His mystical stillness as the ritual unfolded.

***

Have you experienced a ritual that changed you deeply? As I watched, I was being taught how to grieve and honor the dead. I didn’t know how important that would become when Vic died. I’ll need one more post to describe the funeral ritual and how being there transformed my spiritual life. The day was punctuated by the arrival of the Prime Minister of India and many other dignitaries, including the temple elephants. The next day we learned there had been 250,000 people there that day. I’m forever grateful we were allowed to stay and witness. Vic took many photos, most of which are still in slide form. (It’s on my list to have them digitalized and someday I will.)

Have you experienced a ritual that changed you deeply? As I watched, I was being taught how to grieve and honor the dead. I didn’t know how important that would become when Vic died. I’ll need one more post to describe the funeral ritual and how being there transformed my spiritual life. The day was punctuated by the arrival of the Prime Minister of India and many other dignitaries, including the temple elephants. The next day we learned there had been 250,000 people there that day. I’m forever grateful we were allowed to stay and witness. Vic took many photos, most of which are still in slide form. (It’s on my list to have them digitalized and someday I will.)

For earlier posts in this series, beginning with our first visit in 1990, see Out of Control: Pilgrimage to India, 1. Then, Out of Control: Journey to India, Part 2, Journey to India, Part 3, and The Silent Blessing (Journey to India, Part 4). Sri Sankaracharya died on our third visit to India in 1994. Each visit to Kanchipuram, including the last, was about two weeks long.

Wow, that was truly epic Elaine! My heart was in my mouth throughout, most especially when I got to the moment you reveal that Sankara was dead yet posed in that raised chair. Thank you so much for sharing yet another of your Journey to India posts. What an honour it must’ve been to witness all this, I’m blown away by the scenes you’ve painted with words here. My heart opens, wide! These sacred journeys and sacred photographs that you shared with Vic are extraordinary! Yes please, digitalise all the slides, I would love to see them! What precious heirlooms these are for your sons.

Although I didn’t attend myself and could only watch it all unfold on TV, something like 250,000 people also paid their respects to Queen Elizabeth II while she was lying-in-state at Westminster Hall, London, last month. Again, it was extraordinary to witness the whole occasion and to hear so many stories of how the queues were almost twenty-four-hour long yet still her ‘loyal subjects’ came. I think this, along with Princess Diana’s funeral, which prompted my divorce all those years ago, have been life-changing events where the archetypes seemed to come to life before me. Love and light, Deborah.

Thank you, Deborah. I’ve tried to write about this before, but realized I didn’t know enough to write a book about these experiences. Still, I wanted some details preserved and shared for those interested or curious–and I still haven’t shared the “punch line.” I’ll do that in 2 weeks. As you know, I’m not a Hindu or Buddhist or formally any religion. Paul Brunton who wrote about Sri Sankara in ‘A Search in Secret India’ (1934) didn’t belong to a specific religion, but called himself a philosopher. Paul Brunton and his student, our teacher Anthony Damiani, felt we should learn the spiritual truths expressed in many traditions and find our own individual path.

Queen Elisabeth became an archetypal presence (as did Princess Diana). I wish I could talk to Marion Woodman about the outpouring of feeling about the Queen since it was so interesting to hear Marion’s perspective about Diana. (I’d forgotten Princess Diana’s funeral prompted your divorce, but she was a courageous woman who said NO! to patriarchy and being a good little royal figurehead when her husband was in love with another woman.) I hope your new prime minister leads to a period of stability in Britain. I hope we make it through our coming election without violence. I’m writing postcards today reminding people to vote–and not telling them who to vote for. Just vote and participate or we don’t have a democracy. Sending you peace and sunny days as the leaves fall to the earth.

How you tended to Vic with tenderness when he was dying and afterwards, Elaine, has stayed with me. Thank you.

Thank you, Mark. I learned a lot about how to be with death and dying in India. Poor people had funerals right on the street and invited everyone to help decorate with flowers before pushing the cart holding the body to the cremation grounds. No one seemed squeamish about a dead body compared to my Western experience of “hiding” or “making up” the body. Thanks for all you do to help the grieving.

I have never witnessed public mourning as you describe though I’ve seen it at a remove on television with the passing of President Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King, and others. Princess Diana and lately Queen Elizabeth show the worth of sharing our sorrows and paying tribute to public figures we admire and/or identify with.

Now I’m thinking of a verse of scripture that affirms this practice, either publicly or privately: Galatians 6:2 “Bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ.”

Your story, recalled in vivid detail, underscores the great value of expressing grief. Thank you, Elaine.

Thank you, Marian. Public open grief was not familiar to me other than those tragic situations on TV. In India, some mourners sang or played instruments. Others danced and chanted their prayers out loud. Some read about Sankara’s death in the newspaper while the ritual was unfolding in front of them. That was truly amazing! For the sake of brevity and to focus on where this story is headed, I left many details out, but it felt natural to grieve openly in India for someone important like Sankara or for a regular householder where people gathered on the street outside the home to decorate a funeral cart. It was all amazingly public, including the tears. I love the biblical quote you share since I felt in grieving together, the burden was shared. I thought of my poor mother who was alone in her grief because she didn’t want to “fall apart.” In India, no one seemed concerned about falling apart or showing their grief. That felt healthy and natural to me.

What an experience, dear Elaine. The grief has indeed been enormous, though, as I experienced such a mass lamentation, the sense of the core of what the spiritual leader pointed out will be lost after a while. My grieving for Al was to keep myself alone in my room and listen to the songs we heard all the time together.

Thank you again for sharing another part of this exciting journey.

You may be right, Aladin, but the first Adi Sankara died in 750 AD, so this is an old tradition in India. I don’t know what’s happened since 1994, but I know there was some upheaval in the Mutt in recent years. It makes me sad to think of you as a young man grieving for your brother alone. I’m glad you had the comfort of music.

Thanks for sharing this with us Elaine. Here in South Africa, our black population hold very large funerals, where everyone is welcomed and fed. It thus becomes an expensive do – especially when a cow is slaughtered in honour of the deceased. I once attended such a funeral – the cow was in a pit going round and round. A dreadful sight. My house lady who worked for me for 35 + years often went away on weekends to attend a funeral and would bemoan the expenses of it all.

People are fed in Indian funerals, too, although that happened in a different area from where the ritual took place. In India, of course, there was no slaughtering of sacred cows (Lakshmi), but lots of rice and curry. Cows and elephants were part of the temple ritual which I always found moving. They were treated like favored children. I don’t remember elephants or cows on the day Sankara died, but after his death, Vic and I spent many mornings with the temple elephants since we were in India a full week after his death. It was a time of grieving for many while the temple shifted to a new spiritual leader.

Thank you for this truly beautiful and inspiring homage to the archetypal need to respect, honor, and fully grieve the deaths of loved ones. I always think of your description in Leaning into Love of how you ritualized Vic’s death in so many meaningful ways. Thank you for these gifts to those of us who were never taught how to truly and openly experience a death passage in any but the most sterile and restrained ways. I wish I had known how to share that kind of experience with my family when my mother died and hope to be able to change that the next time around.

Experiences in India with Hindus but also with Buddhists taught me the power of ritual. Plus when the Dalai Lama visited our meditation center in 1979 and did a ritual with the children. Marion Woodman also began and closed each workshop with ritual. It felt incredibly important when Vic died and I still take flowers or autumn leaves to his cairn. I’d never experienced anything except Protestant funerals, but I felt the importance of ritual when Vic and I spent time at a Hindu Ashram in Massachusetts–and I learned how much support ritual gave for meditation and life transitions. We’re all learning what helps us as we go. Sankara’s funeral was a huge transformation for me. More to come.

Dear Elaine,

After reading your post and those who responded on your blog, I can’t find any better words than what Jean wrote, “Thank you for this truly beautiful and inspiring homage to the archetypal need to respect, honor, and fully grieve the deaths of loved ones.” While I was at the bedside of both my mother and father when they died in the hospital, I did not have the knowing at that time to bathe their bodies and create ritual. I was fortunate that by the time my beloved mother-in-law died many years later, she was in our home and I was older and wiser.

I have never experienced anything close to what you and Vic did in India with Sankara’s death, and I am very much looking forward to hearing about your transformation at his funeral. Love and gratitude, Anne

I had never experienced anything like it before either, Anne, but we went back three times to spend two weeks each visit sitting in meditation with the sage. The quiet around him was astounding. Somehow, the last trip was equally or more powerful even though he died in the middle.

I’m glad you were with your parents in the hospital, and I’m glad you knew how to add more ritual when your mother-in-law died. We keep doing the best we can and learning as we go. I realized I couldn’t give a full picture of what I learned in one post, plus I haven’t written about the comfort offered by the temple elephants after Sankara’s death. So there will be two more India posts–and that’s all. I’m glad to preserve a taste of this experience but want to return to other issues and not get involved with another long series. Love and blessings to you.