Jo Hockley

Since the 1960s there has been an increasing interest in the psychosocial aspects of end of life care. It could be argued that it has been the hospice movement that has helped to emphasize the importance not only of holistic care of patients but also extending that care to the family. Both of these aspects are now widely used in differing specialties of acute care. Within end of life care, professionals commonly deal with a couple of fundamental issues of psychosocial care, namely: (i) how to use the time after a diagnosis of progressive, incurable disease, and (ii) how long the patient might have to live.

A useful analogy of the uncertainty of time with which both patient and family are faced after a diagnosis of advanced disease is portrayed in the play ‘Shadowlands’, based around the latter part of CS Lewis’s life.

It involves his love for an American writer, Joy Davidman, and her subsequent death from cancer.

The play gives insight into many of the dynamics involved in such a tragedy: dynamics about family, communication, spirituality and dying. CS Lewis, in his helplessness and shock at hearing the extent of Joy’s cancer, asks the doctor how long she has to live. The doctor returns the question with the analogy of a train: “Mr Lewis, he says, you’re looking at a train standing in a station. It may not be moving right now, but trains move. That’s how trains are.”

It is this aspect of the disease trajectory, with special attention to the psychosocial issues for patient and family, that this article will look at, namely:

1. Openness of communication between patient and family and our role as care givers;

2. Factors that enable families to cope with the dying of a loved one;

3. Ways in which we can assess how a family is coping while caring for a loved one who is dying;

4. Being aware of the ‘vulnerable’ within the family unit of someone who is dying.

OPENNESS OF COMMUNICATION ON EMOTIONAL AND EXISTENTIAL ISSUES OF DEATH AND DYING

Before examining some of the more obvious medical literature, there is much in the classical literature and the arts that deepens our understanding of some of the emotional: existential issues for the patient and family facing death.

Edvard Munch is well known for his painting of the ‘The Scream’, which has been used often in end of life care conferences to illustrate the sense of isolation that both terminally ill patients and indeed bereaved relatives might experience.

Right from early childhood Munch’s life was dogged with illness and death, and many of his pictures portray the anguish that he felt. In his short story of ‘The death of Ivan Ilyich’, Tolstoy gives a brilliant literary account of the ‘lack of openness and collusion’ in a family. In the book, Ivan struggles with the growing realization that there is something seriously wrong with him. His family and his doctor, not knowing what to say and believing Ivan does not want to talk about it, isolate him in a conspiracy of silence. They fail to realize that they cannot prevent Ivan’s body from revealing the truth of what is happening. Ivan wants to scream out ‘stop lying!’ but he dares not. Instead, he ends his days in the agony of symptoms uncontrolled, isolated from the comfort of family and friends knowing what he is going through. Ivan could not bring himself to ask and, to Ivan, his doctor and family appeared preoccupied with living.

As professionals in Hospice care, we need to have our intuitive antennae alert to picking up clues and being proactive in our search for unspoken fear. This will give patients and their families opportunity to talk about what they are experiencing and how they are coping.

FAMILIES AS THE UNIT OF CARE AND ISSUES OF COPING

One of the central beliefs within the hospice movement right from its inception in the 1960s is that the family is the unit of care. Over 50 years on, across the spectrum of community and hospital healthcare, there is greater awareness of the needs of the terminally ill patient: the need to control symptoms and the importance of answering questions truthfully. We are also aware of our need to speak to relatives and answer their questions. But, do we connect the two? Do we really consider the patient and the relatives as a ‘family’, together, making the time to organize a family meeting? Or do we see them as two identities, as the patient and the relative coping as best they can, sometimes in semi-isolation.

We have to understand that what happens to a patient has a direct impact on all members of the family, not only the spouse, but also the children and indeed the parents of the patient in some situations. The importance of a family meeting cannot be emphasized enough and in some circumstances can make a considerable difference to how families cope. Besides the emotional strain of living with the threat of a terminal illness hanging over a family, and the importance of communication, there is the adjustment of changing roles as the disease progresses. Even if there is complete openness and honesty within a family, it is nonetheless sometimes difficult to accommodate the necessary role adjustment. Any role shift is likely to place added burden on the other family members.

As health professionals, it is crucial to remember that we are there to help. Helping a person, a couple or a family to regain control of what often seems to them to be an uncontrollable situation can call for reasonably innovative thinking. In some circumstances it may mean taking a more direct initiative, such as admitting a patient for respite care because of a family’s exhaustion. However, this is always with the intention of handing back the control and autonomy to the family once the immediate crisis has passed.

ASSESSING FAMILY SUPPORT

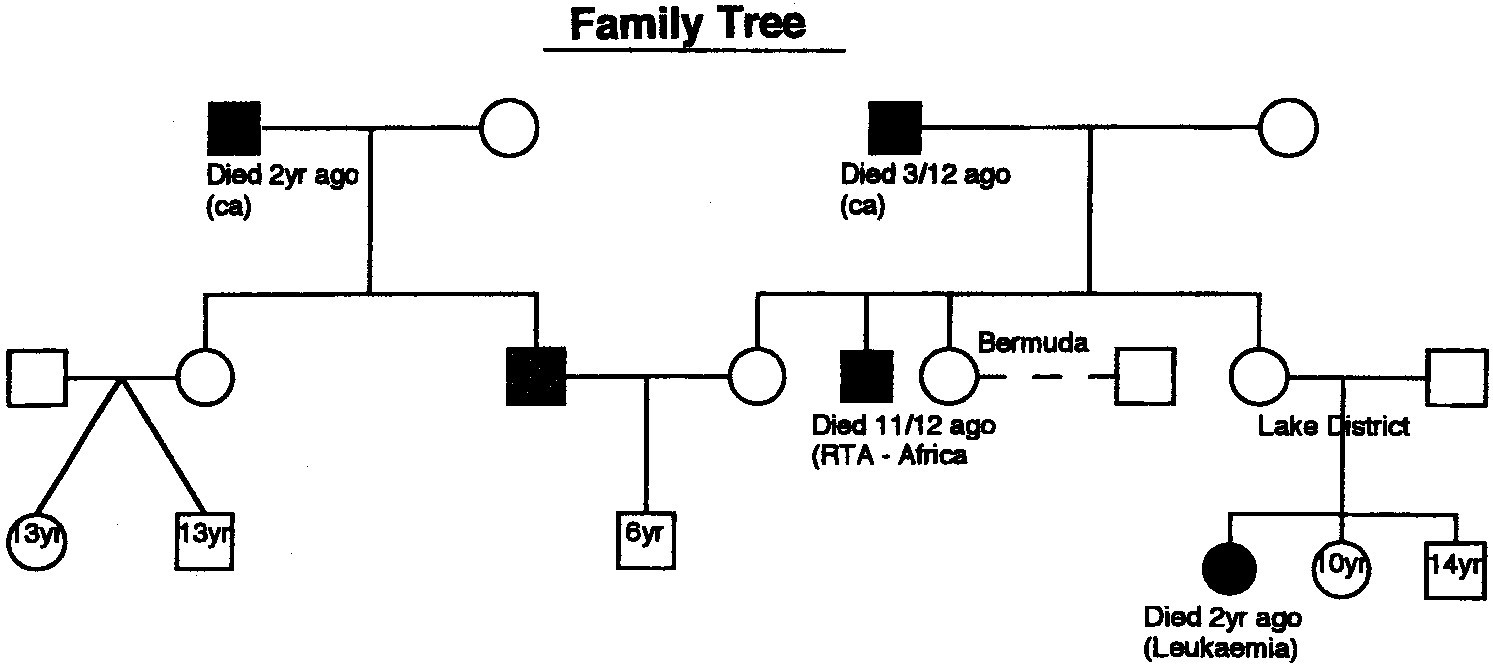

Sketching out a family tree or genogram with a patient who is terminally ill is a practical way of establishing what support there is within the family. By drawing a genogram with the patient one can determine what support there is or is not within the family. It also identifies who might be at risk in the family and whether extra specialist support in the form of nurse specialists, social workers or psychologists might be helpful.

The following case study and family tree (Figure 1) of a 45-year-old man, Simon, who had carcinoma of the lung is an example of the importance of understanding the situation from the family viewpoint.

Case study 1

Simon was married. He and his wife had a 6-year-old son, Jamie, who was conceived 14 years after being told they would never have children. The child was understandably very precious. On both sides of the immediate family there was little support. Simon had a sister and mother, but his own father had died 2 years previously from cancer. There had been several deaths in the family: Simon’s father in-law had died 2 months ago from cancer, and his brother in-law had died from a road traffic accident 11 months previously. His wife had requested to see someone after their son had asked her whether ‘Daddy was going to die?’ ‘No, of course not!’ she had said quickly and then regretted it. She felt that she had betrayed his trust in her. The family lived 60 miles away from the hospital where Simon was now a patient and she was facing the situation that ‘if Daddy wasn’t going to die’, why was she staying at the hospital. Simon was extremely ill and it was anticipated by the doctors that he might not live the weekend. The wife was very strong; she had to be to have coped so well with all the recent losses that she had been through.

As we compiled the family tree together, she suddenly realized the impact of the losses on Jamie, who had seen both grandparents and an uncle die within the last 2 years. All male in gender. For him this was a large majority of his acquaintances, and now Daddy was ill: was he to die and if so what about me and Mummy?

I never specially saw Jamie but guided Simon’s wife on how to talk further with Jamie, giving her booklets to help to back-up what we had talked about together. Often the best people to talk to children are their parents, but they often need considerable guidance and help from professionals to know how to start such a difficult conversation.

If children are excluded from being involved with what is going on, especially if they have a strong relationship with the dying person, it may become difficult for them to accept the death. Being honest with a child who is asking difficult questions and the showing of emotion are not detrimental as long as the child feels a sense of control in the situation: a hand being held or an arm around them. For a child to be excluded from this process will only make them feel isolated and alone: children are always aware of the atmosphere around them even though they might pretend otherwise.

AWARENESS OF THE VULNERABLE CHILD IN A GRIEVING SITUATION

Kliman lists eight circumstances where, if two or more occur together around the time of the death of a parent, the child may be in danger from psychological disturbance later in their development:

1. The child has suffered a loss under the age of 4 years.

2. The child already has psychic behaviors.

3. There has been a change of environment;

4. The surviving parent develops pathological grief;

5. There is increasing physical intimacy with the surviving parent;

6. A death has been caused through the birth of a child;

7. The family has concealed the disease from the child;

8. Terminal illness has resulted in physical deformation or psychic problems.

As healthcare professionals who have access to research and information, we have a duty to pass on and to help families cope with dying. In the past, certain community rituals were passed down and supported people through the death of a loved one. Now, more and more the same support is not available. Patients and families are seeking help and information and we need to be equipped with the necessary advice. The work that can be done before someone dies is fundamental in helping a grieving family to cope. However, it is not about taking over but more about empowering and helping a patient and family to regain some control.

In summary, therefore, it is important that awareness of the family unit as a whole is considered. A good family assessment should be performed alongside other health professionals such as social workers. Caring for the dying patient and his or her family requires the efforts of the whole multi-disciplinary team: the nurse, the CNA, social worker, the doctor and the chaplain.

Finally, it is how we communicate with the patient in the context of the family that hopefully allows death to become ‘the discreet but dignified exit of a peaceful person, from a helpful society, without pain or suffering and ultimately without fear.

REFERENCES

1. Sankar A. Ritual and dying: a cultural analysis of social support for caregivers. Gerontologist 1991; 31: 43–50.

2. Hockley J. Rehabilitation in palliative care—are we asking the impossible? Palliat Med 1993; 7 (2 Suppl): 9–15.

3. Nicholson W. Shadowlands. London: Samuel French, 1989.

4. Tolstoy L. The Death of Ivan Ilyich and other stories (English translation). London: Penguin, 1960.

5. Buckman R. I don’t know what to say: how to help and support someone who is dying. London: Macmillan, 1993.

6. Rogers CR. On becoming a person. London: Constable, 1961.

7. Kearney M. Palliative medicine—just another specialty. Palliat Med 1992; 6: 39–46.

8. MacLeod R. Learning to care: a medical perspective. Palliat Med 2000; 14: 209–16.

9. Rathbone GV, Horsley S, Goacher J. A self-evaluated assess- ment suitable for seriously ill hospice patients. Palliat Med 1992; 8: 29–34.

10. Powazki RD, Walsh D. Acute care palliative medicine: psy- chosocial assessment of patients and primary caregivers. Palliat Med 1999; 13: 367–74.

Leave a comment