Genealogy has immense value for older adults, offering connections to the past, present, and future.

As a lawyer, Leonard Kofkin, 89, was no stranger to yellow legal pads. And that’s what he turned to 53 years ago when his aunt brought him an overlooked shoebox of family photos and documents.

Kofkin grew up in Chicago, thinking his immediate family was all the family he had. When he first opened the box, Kofkin says he felt a wave of emotions. “I was looking at people who I knew or believed had died many, many years before. My great-grandmother, great-grandfather, and cousins that I had never seen before. It was eye-opening, nostalgic, sad, but I was elated. I just had to stay with it,” he says.

Someone had written the subjects’ names and relationships on the back of each photo. To Kofkin, most of whose family had died in the Holocaust, these were invaluable clues. The box also contained postcards and letters that Kofkin used to chart major events and familial whereabouts — all on his yellow legal pad.

The shoebox set the Schaumburg resident on a worldwide hunt that eventually led him overseas and grew his modest family tree from a handful of branches to 679 relatives in 80 countries, dating back to 1760.

Craig Pfannkuche, corresponding secretary of the Chicago Genealogical Society, says that many people who get hooked on genealogy are looking for something beyond themselves. “People want to know where they fit into history,” he says.

For Pfannkuche, the spelling of his own last name initially piqued his interest in genealogy when he was a teenager. That personal curiosity evolved into a career as a historian and genealogist.

Branches to trees

Genealogy — the study of family ancestry — is one of the most popular hobbies in the U.S. The internet has enabled connections and research like no time in history, and DNA testing kits are a booming business. The DNA service 23andMe, for example, has sold more than 12 million DNA kits since 2006.

Researching family history gives people a sense of meaning and belonging. It also creates a legacy for other family members.

Matthew Rutherford, genealogy and local history curator at the Newberry Library in Chicago, says people feel drawn to family research because they want to explore their personal and family identities. Many, like Kofkin, also have “curiosity about the past when family stories have been hidden or inconsistent,” Rutherford says.

But at least Kofkin had a place to start: his shoebox. “It took a really long time. It’s not something I spent all day on, but every chance I got, I would reach into the box, and see where they fit into my drawings of trees,” he says.

This was the early 1970s — pre-internet — and the lawyer-turned-genealogist spent the next two years sketching out his family tree.

“Every family has stories,” Pfannkuche says. “They may be buried, but they can be dug up. They can be found. It connects you to the history, to the function of the nation.”

In the early 1900s, Kofkin’s paternal grandparents had emigrated to the U.S. to work in an Erie, Pennsylvania factory. They’d come from the same town in Estonia but hadn’t known each other there.

Rutherford says researchers often gain a better understanding of why their ancestors made the decisions they did, even if such knowledge wasn’t the researcher’s primary goal. This insight can lead to fuller unexpected sympathy or empathy.

“Suddenly, the tales of great-grandma’s cold manner make more sense or are more forgivable, for instance, once it’s known that she lost four children under the age of 5 that she never talked about,” Rutherford says.

On an emotional level, he adds, “Learning one’s family history generally leads to more confidence about one’s place in the world.”

That was true for Kofkin, whose name going back centuries roughly translates to family of Kof. “I was really proud of being Estonian and being the first-born son of a first-born son, perhaps the last to carry the unique surname of Kofkin,” he says.

The surname was so unique in fact, that whenever Kofkin traveled across the U.S., he’d open the local phone book to see if he could find anyone else with his family name. Over the decades, he found only one: a psychiatrist in New York City, whose family had come from Latvia. Although that meant they weren’t related, the two became close friends.

Information everywhere

While Kofkin followed his curiosity through phone books, there are many avenues to start building a family tree. People can begin with what they know about themselves and talk to family members about their knowledge of past generations. U.S. census data, Ellis Island logs, and genealogy websites hold a wealth of information. And many organizations — from local libraries to genealogical societies — offer ancestry classes.

Pfannkuche recommends consulting the reference librarian at your local library. Most local libraries have access to ancestry.com, census reports, and local newspapers. You can also join your local genealogical society.

In his own research, Kofkin says he found that “one door opens, and you go through it. And then another door opens, and you go through that one.”

He wasn’t the only one searching for open doors. In Israel, a woman gave her friends a note whenever they traveled to the U.S., asking them to publish it in Yiddish-language newspapers. She was looking for any information about her brother, Leopold Kofkin. A friend of Kofkin’s saw one of the classified ads in 1984 and mentioned it to him.

“I wrote to the person in Israel, whose married name I did not recognize, explaining that I was the son of Leopold and asking who she was,” Kofkin says.

A letter returned to him a few weeks later, from a woman named Ester — his grandfather’s youngest sister. She was only 3 years old when her brother emigrated.

Kofkin says he was thrilled to learn of such a close relation. “Oh my goodness! Here’s somebody still alive. She started sending me her charts and little notes about what happened. If we had all been together, she would’ve been a significant part of the family.”

Building a legacy

Getting involved in genealogy research can be a life-changing pursuit for older adults, as Kofkin has discovered. Yet, many don’t start their research until they’re older.

“As we get closer to the end of our lives, we want to leave a record, not only of our lives but also of the lives of older generations whom we knew or heard of,” Rutherford says.

This creates a trail for future ancestors to discover and follow. “So often, I’ve heard, ‘I’m doing all this for my grandchildren. They’re not interested yet, but they will be someday,’” Rutherford says.

There are social and mental health benefits, too. “Genealogy is like a puzzle, so genealogists are always thinking and strategizing in their research,” Rutherford says. “Researching one’s family history has to be at least as good for the mind as crossword puzzles.”

Genealogists tend to be very social and form communities both online and offline, he adds. “We see this often at the Newberry, where one genealogy researcher will jump in to help another even when they didn’t know each other previously.” Those connections are particularly valuable for older adults staving off loneliness.

“It keeps them alive, thinking, analyzing, looking up,” Pfannkuche adds. “If you’re in assisted living, querying your family keeps you connected out there. And if you’re still mobile, it gives you all kinds of places to go visit, a sense of adventure.”

Ester was 84 when she and Kofkin began corresponding, and within a few months, he visited her in Israel, learning about the small part of his family that had survived the Holocaust and about those who did not.

Though Ester was the first of his grandfather’s family that Kofkin met, she would be far from the last. Through Facebook, a cousin in Israel messaged him, and he traveled to meet her, her daughters, and their families.

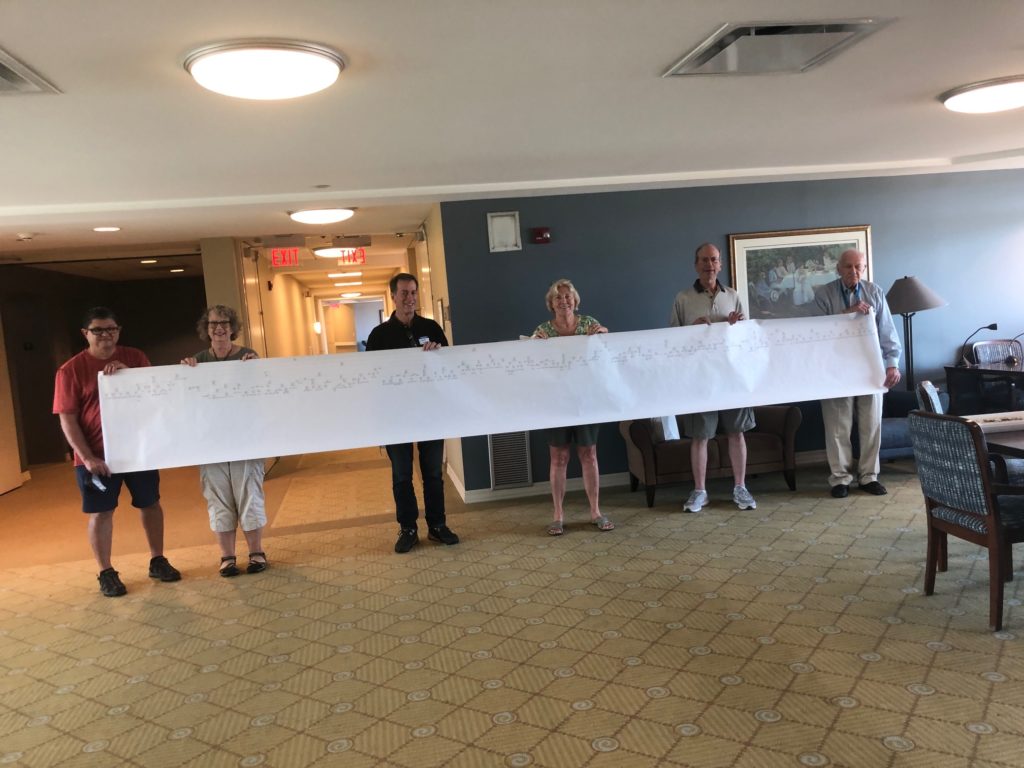

Whenever Kofkin meets with family members, he brings his family tree charts, revealing to them their many relatives worldwide. “Every time I meet one of my family members I am greeted with such kindness and generosity because I bring them the history of their family that they never had,” Kofkin says.

Charting lines

Building such large, interwoven charts can get unwieldy and may intimidate many new to ancestry work. “It’s amazing how quickly the names and ancestors can multiply,” Rutherford says.

To keep the dozens to thousands of names sorted, numerous record-keeping systems exist. Some researchers turn to online genealogy services like ancestry.com or FamilySearch. Others use private software, such as Roots Magic or Family Tree Maker. And still many researchers prefer a paper system. “All are fine. The key is to find one you like and stick with it,” Rutherford says. “Having your data recorded will give you peace of mind and allow you to readily move around among family lines as you pursue your research without having to keep track of details.”

While Kofkin reveled in sharing his family charts with his relatives, he also struggled in his research. He had difficulty tracking down female family members who had married and adopted their husbands’ surnames. And he found that many branches of the family had altered the spelling of their last name. Then there were the people who immigrated to the U.S. from Estonia, Latvia, and other regions of the USSR, but who were simply labeled as Russian.

During the Soviet era, Kofkin traveled to Estonia, but he couldn’t look up any relatives there. “The Soviets didn’t have phone books,” he says, noting that the Soviet government was paranoid about people communicating with Americans. “But I could visit and dream about [family], think about them.”

Pfannkuche says the biggest challenge in genealogy research is a loss of records. Chicago records from before the Great Fire in 1871 are scarce, and Illinois didn’t begin keeping death or birth records until 1916. War-ravaged areas also have lost mass amounts of records. “A lot of records have been destroyed over the years, so then you have to look other places. You can work around it. Go to the newspapers, visit the cemetery,” Pfannkuche says.

Similarly, Rutherford adds, “Certain groups of folks face challenges based on historical record-keeping practices.” Enslaved African Americans, for instance, typically weren’t recorded by name in documents.

Time creates another challenge, because genealogy research requires so much of it. “A lot of genealogy material is not online, so it takes time to visit libraries and archives where the information and records are kept,” Rutherford says. And even if researchers find information online, they may want to see certain records inperson to verify their accuracy. As a result, Rutherford says, genealogy research “is best suited for those whose schedules allow them to engage with it for at least a few hours at a stretch.”

Past to future

Through the challenges, Kofkin persevered. Internet searches eventually revealed relatives living in London. Kofkin traveled there to meet a cousin in 2005, and another cousin, visiting from New Zealand, joined too.

“The two cousins at lunch had not seen each other for 40 years, and so that meeting had another significant dimension,” Kofkin says. “My bringing new and formerly unknown family members together occurred many times over the years and always was a satisfying aspect of my genealogy work.”

And it turned out that he and the Kofkin he’d found in New York were related after all: cousins who share a great-grandfather. Kofkin’s great-aunt had helped him deduce that the family had originally come from Belarus, not Estonia. The New York Kofkin also had traced his ancestry to Belarus.

Kofkin then hired a professional genealogist, fluent in Russian, who could travel to Belarus and do more digging.

“Sometimes the only thing you can do is go to where the archives are kept by the governing country. [The professional genealogist] was one shot, and it was worth it.,” Kofkin says. Through records she found in Belarus, she traced Kofkin’s family lineage back to the 18th century.

Over the years, Kofkin has kept his family apprised of his findings via email updates. The email list has grown to 75 related subscribers from all over the world, and Kofkin says he always looks forward to chances to see them in person.

Kofkin, now a widower, has a daughter and two sons who support his family research and the extensive family they’ve gained, but he says no one has volunteered to take over the project. He holds out hope, though, mentioning a grandson who recently asked him questions about their ancestry.

Or maybe his work will make its way into another shoebox, for someone else to discover further down the family line. Someone Kofkin might not have even met yet.